The DLR SpaceBot Cup 2013

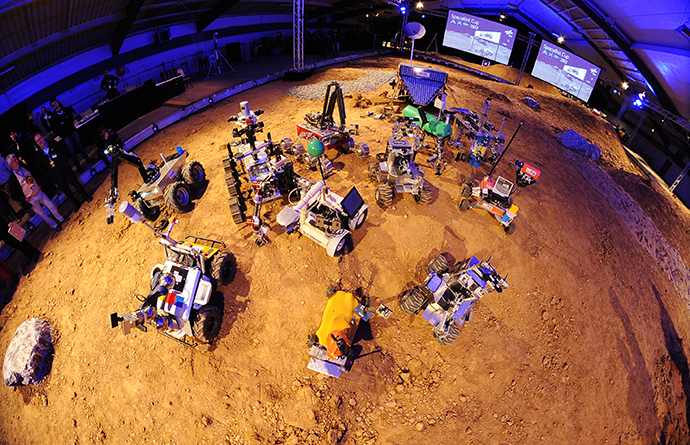

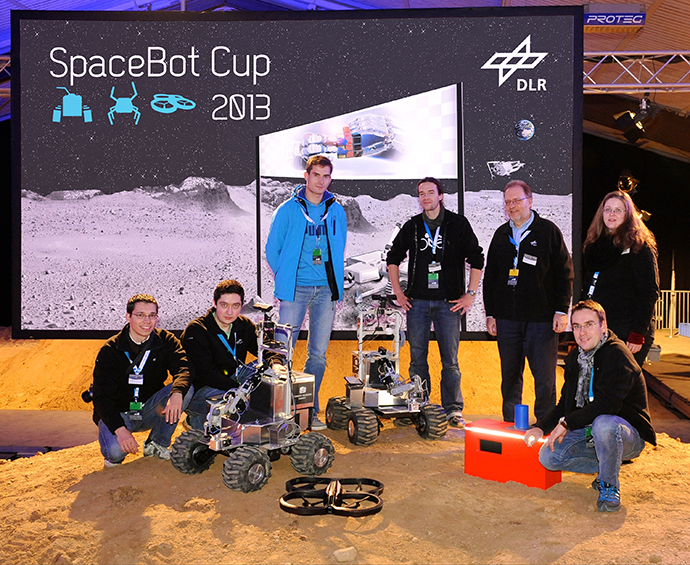

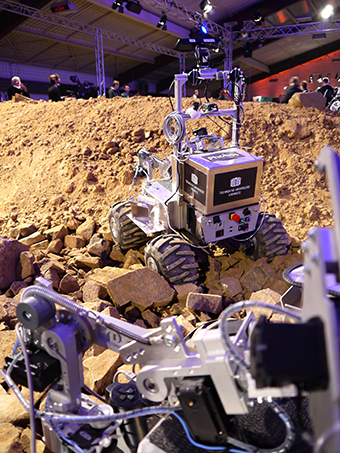

In 2013, ten teams from German universities and research institutes participated in a national robot competition called SpaceBot Cup, organized by the DLR Space Administration. The robots had one hour to autonomously explore and map a challenging Mars-like environment, find, transport, and manipulate two objects, and navigate back to the landing site. Localization without GPS in an unstructured environment was a major issue as was mobile manipulation and very restricted communication. We entered the competition with a multi-robot system of two rovers operating on the ground plus a quadrotor UAV simulating an observing orbiting satellite. We relied on ROS as the software infrastructure. Despite (or because of) faults, communication loss and break-downs, it was a valuable experience with many lessons learned.

Our iSAIRAS14 paper describes the robot and aspects of our strategy in more detail:

-

Phobos and Deimos on Mars – Two Autonomous Robots for the DLR SpaceBot Cup In Proceedings of International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence, Robotics and Automation in Space (iSAIRAS), 2014.

In 2013, ten teams from German universities and research

institutes participated in a national robot competition

called SpaceBot Cup organized by the DLR Space

Administration. The robots had one hour to autonomously

explore and map a challenging Mars-like environment,

find, transport, and manipulate two objects, and navigate

back to the landing site. Localization without GPS in an

unstructured environment was a major issue as was mobile

manipulation and very restricted communication. This paper describes our system of two rovers operating on the

ground plus a quadrotor UAV simulating an observing orbiting

satellite. We relied on ROS (robot operating system)

as the software infrastructure and describe the main

ROS components utilized in performing the tasks. Despite

(or because of) faults, communication loss and breakdowns,

it was a valuable experience with many lessons

learned.

In 2013, ten teams from German universities and research

institutes participated in a national robot competition

called SpaceBot Cup organized by the DLR Space

Administration. The robots had one hour to autonomously

explore and map a challenging Mars-like environment,

find, transport, and manipulate two objects, and navigate

back to the landing site. Localization without GPS in an

unstructured environment was a major issue as was mobile

manipulation and very restricted communication. This paper describes our system of two rovers operating on the

ground plus a quadrotor UAV simulating an observing orbiting

satellite. We relied on ROS (robot operating system)

as the software infrastructure and describe the main

ROS components utilized in performing the tasks. Despite

(or because of) faults, communication loss and breakdowns,

it was a valuable experience with many lessons

learned.

Outcome

Due to the extremely ambitious task, none of the ten participating teams was able to fulfill all aspects of the competition. This reminded us of the first DARPA Grand Challenge where results were a bit disappointing at first, but largely improved during the second contest two years later.

The press dubbed our team the „most lively“ of all, but the jury refused to decide on a final ranking or even publish how many points each team gained. We felt our performance was comparably good and we would have finished among the best teams – had there been a final ranking. We had three working autonomous systems in the simulated Mars environment. Check out this cool video, showing the event from the perspective of the robot. The DLR also produced a pretty cool trailer video showing our team and the the robots.

The faulty and unreliable communication between the simulated ground control station and the robots was a more severe issue than the participants anticipated. All teams experienced massive problems when trying to send commands to their robot or receive data from it. This lead to the very unpleasant situation that some the participating teams could not even send a start command to their robot. This situation will surely be fixed for the next SpaceBot Cup 2015, so the researchers and robots can demonstrate their capabilities.

Our Conclusions

We have seen our systems working well in principle. They worked (mostly) in the lab and (sometimes) in the competition. The problem is robustness. The hardware of the rovers was fine for this purpose, sensors can be improved with current technology (better cameras, laser scanners), ROS has some major software engineering issues, but is not the bottleneck.

One of the main hurdles in achieving more robust autonomy is poor exception handling. Handling exceptions on all levels of the control architecture via recovery behaviors and contingency modes is the key to a robust and truly autonomous long-term operation of any robot. While the actual mission plan is often rather straight forward, designing and implementing these exception handling routines in the control architecture is very tedious. SMACH in its current form (even with our extensions) is not well suited to control the behavior of a robot in a complex environment with many possible error sources.

Another way to increase overall robustness is to use multiple robots that cooperate in good times but are able to work independently if other robots or communications fail. Here too, the key is exception handling and improved situational awareness, and we will concentrate on these issues in future work.

The SpaceBot Cup – as all competitions with a firm deadline – boosted our productivity and we hope to present some new ideas at a possible SpaceBot Cup 2015.

The team of Chemnitz University of Technology competes again in the SpaceBot Cup 2015. Best wishes for that exciting endeavor!